Invisibility by design: how inaccessible services reinforce exclusion – and how we can break the cycle

6 minute read

Inaccessible services don't just exclude, they erase. In this piece Danny explores how digital inaccessibility creates a self-reinforcing cycle of exclusion, invisibility, and missed opportunities. With the European Accessibility Act now in effect and AI reshaping our tools, it’s time to break the cycle, and build inclusion into the foundations.

What is the inaccessibility cycle?

The social model of disability reminds us that disability isn’t caused by impairments themselves, but by the barriers society creates. Nowhere is this more visible than in digital services.

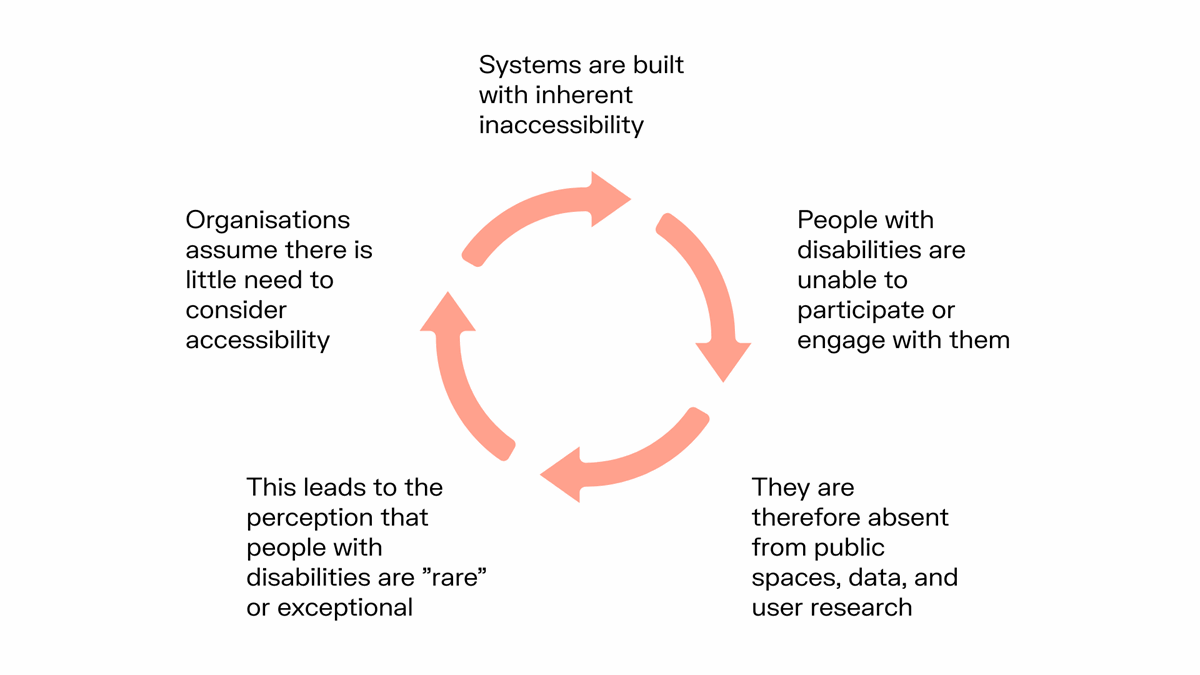

A persistent – and damaging – result of these barriers is what we call the inaccessibility cycle:

- Services are built with inherent inaccessibility.

- People with disabilities are unable to participate or engage with them.

- They are excluded from user research, feedback loops, and public visibility.

- This lack of visibility reinforces the idea that disabled people are rare or “edge cases”.

- Organisations wrongly conclude there’s no need to prioritise accessibility.

- And the cycle continues.

This isn’t usually driven by intent. It’s often a byproduct of systemic exclusion, cultural perceptions, and outdated assumptions. Most people want to do the right thing. But when exclusion is built into the foundations, it becomes invisible. That invisibility becomes self-reinforcing making it harder to notice, harder to challenge, and easier to repeat.

The cycle of inaccessibility — how inaccessible digital services continue to exclude people when inclusive practices are not embedded.

The digital exclusion landscape

To understand why this cycle persists, we need to acknowledge the current state of digital accessibility today.

Take ecommerce – something millions rely on daily. Accessibility should be a given. Yet research paints a different picture.

According to the Click-Away Pound report, 82% of disabled users will abandon a purchase if they encounter a barrier. While the Purple Pound states that 73% of potential disabled consumers face barriers on more than a quarter of websites they visit. That adds up to an estimated £2 billion in lost revenue per month – despite disabled households in the UK holding over £274 billion in spending power annually.

WebAIM’s Million project echoes this. Their 2025 analysis of the top 1 million homepages shows that ecommerce sites have the highest average number of automated accessibility issues per page (71, to be precise). Out of 29 industries, ecommerce ranks lowest – behind even gambling, sports, and adult content.

And it isn’t a one-off. The shopping category has been in the bottom 3 ranks since this metric was introduced.

What's more, of the 50.9 million issues found in that study, a staggering 96% fall into just six basic categories:

- Low-contrast text (on 79.1% of homepages)

- Missing alt text for images (55.5%)

- Missing form labels (48.2%)

- Empty links (45.4%)

- Empty buttons (29.6%)

- Missing document language (15.8%)

Many of these are easy, low-cost fixes. The fact that they’re still common suggests accessibility isn’t just forgotten, it’s being sidelined.

And ecommerce is just the start. During COVID-19, inaccessible vaccine booking systems left many screen reader users, people with cognitive impairments, and those without fast internet locked out of critical services. Inaccessibility, in these cases, was more than frustrating – it put lives at risk.

The UK Government also released a report on accessibility in the private sector in the last week, after surveying over 3000 people with disabilities. The findings from this report reaffirms all of the above–many sectors, particularly retail, finance, tourism and leisure still pose significant barriers, especially in digital experiences.

Asking better questions

Breaking the cycle starts by reframing the questions we ask.

Too often, accessibility discussions begin with medical labels: “How many of our users are blind?”. It’s well-meaning, but limiting. It narrows the conversation and overlooks how people actually use digital tools.

Here’s a better perspective:

- Around 43 million people are registered blind globally

- However only around 7% of them have no light perception at all

- But over 2 billion people have some form of vision impairment

- Many use screen magnifiers, large text, contrast settings, or browser zoom – and don’t identify as disabled

Instead of diagnosis-driven questions, it’s best to ask about tools, habits, and adaptations:

- Do users increase their device text size?

- What assistive tools (like screen readers or magnifiers) are people using?

- Can our service be used without a mouse?

These questions yield better insights – and in turn better design decisions. After all, inclusive design isn’t about fixing problems for a small group – it’s about understanding that different people use the same tools in different ways.

And remember: you don’t have to identify as disabled to benefit from accessible services. That’s precisely why it matters.

Why visibility matters

Better design starts with better questions. But real inclusion depends on visibility.

Consider this: how are peoples access needs understood and represented in your organisation and work?

- Do they appear in your customer feedback?

- Are they present in your user research panels?

- Are they reflected in your user personas?

- Are they part of your communications and ways of work?

- Are they part of your recruitment strategies?

When people with disabilities are missing from these spaces, it's not because they don't exist – it's often because they gave up trying. If someone can't participate, they won’t complain – they’ll go elsewhere.

And perhaps the most critical area of visibility is your hiring process. If you’re not building teams that include people with lived experience of disability, your culture will never fully reflect their realities. If people with disabilities aren’t involved in shaping services, then their needs will always be an afterthought.

As the disability rights movement puts it: “Nothing about us without us.”

And as with ecommerce, silence doesn’t mean success. If you're not hearing complaints about accessibility, it might be because disabled people already left. Not because everything works – but because it doesn’t.

This has happened before

The inaccessibility cycle is not a new phenomenon – it’s just digital now as well.

Let us not forget that only as recent as the late 19th to mid-20th century, many US cities enacted what became known as Ugly Laws. These laws made it illegal for people with visible disabilities to appear in public. They framed disability as something shameful or inappropriate – something to be hidden.

It’s a disturbing history. But it reminds us: when we fail to design for inclusion, we continue this legacy of exclusion – just through different tools.

Today, we no longer fine people for how they move through the world. But exclusion persists – just in more subtle, systemic ways. When a screen reader can’t navigate your website, when a form can't be completed with a keyboard, when your service doesn’t consider disabled users at all – we’re not criminalising disability, but we are disappearing it.

Modern tools may be digital, but the outcome is the same: exclusion through invisibility.

We must confront these parallels if we’re serious about change.

The business case (and the legal one)

We’ve talked about ethics and lost revenue. Sometimes even that isn’t enough. In accessibility, we often reference the carrot and the stick:

- The carrot: financial gain, brand reputation, inclusive culture.

- The stick: legislation and compliance risks.

Just as outdated laws are removed, new legislation is introduced. For years, EU public sector bodies have been bound by the 2018 European Accessibility Directive. But now the European Accessibility Act (EAA) is in effect, with the deadline having passed on 28 June 2025.

The EAA applies to many industries – banking, ecommerce, telecoms, transport, and more. It sets a new baseline: exclusion now equals non-compliance.

But don’t treat this as a box-ticking exercise. See it as an opportunity to build better from the start – to embed inclusive design into how you work. Compliance may get you to the start line – inclusive design gets you to a better product.

What keeps the cycle going?

The barriers aren’t just technical – they’re often cultural too, such as:

- Unconscious bias: Media often portrays disability as rare, tragic, or villainous – skewing perception.

- Missing analytics: Web analytics don’t capture who couldn’t access your service or dropped off due to poor design. Absence of data isn’t absence of need.

- Lack of lived experience: Hiring gaps mean many teams build services without ever considering how users with different abilities might interact.

- Misconceptions about cost: There’s still a stubborn belief that accessibility is expensive or a “nice-to-have.”

Here are some of the myths that keep the cycle going:

| Myth | Truth | Back it up |

|---|---|---|

| “We don’t have disabled users.” | You would – if they could use your service. | 1 in 5 people live with a disability. Add older adults, temporary impairments, and unregistered adaptations – the number is much higher. Most people will face accessibility issues at some point in their lives. |

| “It’s too expensive.” | Inaccessibility costs more. | Fixing issues in production costs 30x more than during design or development. Add potential legal risk, maintenance costs, and the long-term reputational and market benefits, and it's obviously the smarter option. |

| “We’ll fix it later.” | Retrofitting is harder and often never happens. | Many accessibility statements haven’t been updated since 2019. “Later” too often means “never.” |

Accessibility at any scale

This isn’t just for big orgs with big budgets. Small teams can make a big difference, by implementing some of the following practices:

- Use axe DevTools, WAVE, or Siteimprove to scan for common issues

- Test one journey with keyboard only

- Add basic accessibility checks to QA or code reviews

- Include assistive tech users in usability testing

- Build accessibility into design systems or component libraries

It’s really about emphasing accessibility as a shared effort – not just the developer's responsibility.

Why we need to break this cycle now

With the focus shifting to technologies next biggest shift in AI, we must address this before we extend the cycle with another inaccessibility loop that we risk repeating.

The AI revolution brings opportunities, but it also brings risks for accessibility. AI has the power to remove barriers – but only if we train and deploy it responsibly.

Unfortunately, we’re already noticing that accessibility is missing from AI development. AI-driven tools are being used to generate alt text, test interfaces, and even predict accessibility issues. But these models are frequently trained on biased data, meaning they make mistakes. Critical mistakes. Like self-driving cars are not being trained to deal with wheelchair and mobility scooters.

We risk automating exclusion at scale if we don’t include disabled voices in the design, testing, and governance of AI tools. AI systems often don’t recognise adaptations like screen reader use, or they produce inaccessible outputs (e.g., images without proper text descriptions).

Inclusive design in AI must include:

- Training datasets that reflect disabled users

- Guardrails to prevent harmful assumptions

- Testing with real assistive tech and lived experience

- Transparency in how outputs are generated and evaluated

AI can help break the inaccessibility cycle – but only if inclusion is a design input, not an afterthought.

The future we’re building

So, what if we did it differently?

What if accessibility wasn’t an afterthought, but a foundation?

Legislation like the EAA gives us a rare unified momentum – a moment to shift habits, budgets, and attitudes alike. Because the truth is: if we don’t break the cycle, we continue to build in systemic exclusion.

It’s not about fixing something for a small group. It’s about removing barriers for everyone, starting with those most often excluded.

And we’ve seen what’s possible when we design for the edges. Take Sam Farber, who designed kitchen tools his wife could use despite arthritis. His OXO Good Grips range, made for the edges, became the standard for everyone.

If we don’t intentionally design for inclusion, we’ll unintentionally design for exclusion. Accessibility isn’t about checking a box. It’s about seeing who’s been left out – and doing something about it.

That’s the future we can build. But only if we break the cycle.