The most overlooked accessibility issue in digital design

5 minute read

Across more than a billion websites, one particular accessibility barrier is everywhere — but all too often no one notices it. Designers miss it, content creators overlook it, and yet it’s the most frequently reported issue in audits. This article explains why it’s such a problem, what WCAG says about it, and how new research is shaping better approaches

If I asked you to name the accessibility feature that websites most often fail to include, what would you say?

What do you think it is?

Would you say it was alt text? That would be a reasonable guess, because missing or inadequate alt text is in fact a common problem. But according to WebAIM’s annual evaluation of home page accessibility, alt text comes in second.

Look at the first example here and see where you think the problem might lie.

This is example 1

Can’t find an accessibility issue in that example? See if the next one makes it clearer.

This is example 2

Do you see it now? If not, maybe this third example will remove all doubt.

This is example 3

What it is

The problem, as you’ve probably realised by now, is that the text is hard to read — because it’s too light for its white background.

How we can recognise and avoid it

Fortunately, we have something to help us avoid this problem. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) provide minimum contrast requirements as part of their Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). First published in 1999 and now on version 2.2, WCAG is an international standard under the aegis of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and is designed to help people improve the accessibility of websites and other digital content. The WCAG “success criteria” (SCs) specify accessibility requirements and aid in testing compliance. Pertinent to the topic of this blog post, SC 1.4.3, Contrast (Minimum), requires normal-sized text to have a contrast ratio of at least 4.5 to 1 against its background and requires large or bold text to have a ratio of at least 3 to 1.

In all of the examples at the beginning of this article, the text is too light — even the first one doesn’t quite meet the requirement.

The second example has a contrast ratio of only 2.74 to 1, and the third has a paltry 1.78 to 1. That’s why the second one was probably noticeable and the third one jumped out at you. Thing is, though, at 4.14 to 1 even the first example lacks enough contrast to meet the requirement.

Surprised? Maybe you have excellent vision and you can read all of those examples easily. Maybe it would not occur to you that there might be an issue with their contrast. There’s a likely reason the WebAIM annual test consistently finds colour contrast to be the most common accessibility problem — people (Web designers and developers in particular) don’t think to check for it because they themselves can read the content perfectly well and they are unaware of this particular accessibility issue.

W3C developed WCAG 2.2 to promote accessibility in digital design. (I say “promote” rather than “ensure” because guidelines and standards by themselves, even if scrupulously followed, cannot guarantee 100% that a site is accessible to absolutely everyone.)

How this contrast thing works

In simplest terms, the WCAG contrast ratio between two colours is the brightness of the lighter colour divided by the brightness of the darker one. When text is displayed on a solid-coloured background, computing the contrast ratio is straightforward. The calculation becomes complicated, though, when text appears on top of images or other complex backgrounds, especially if some parts of the background provide adequate contrast with the text whilst other parts do not. And even if the contrast is compliant over all of a complex background, such a background can still distract the eye and make the text harder to read.

Sadly, the WCAG contrast formula isn’t perfect

WCAG isn’t the final authority on contrast, though. Its algorithm draws on a simplistic model of relative brightness, which experts say contains major weaknesses. In particular, The WCAG contrast formula overlooks nuances in the ways in which people perceive colours and contrasts (including some types of colour vision deficiencies), and it neglects device differences and environmental conditions such as glare and ambient lighting. It also fails to give adequate consideration to the size and weight of text.

Enter APCA, the Accessible Perceptual Contrast Algorithm. This approach, created by Andrew Somers of Myndex Research, takes into account the nuances that the current WCAG algorithm does not, and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is working towards including it in WCAG 3.0. It replaces the simple brightness ratio with a more complex perceptual model that is closer to how we see. Its "lightness contrast" ratio — Lc — considers not only font size and weight but also whether the text is light on a dark background or dark on a light one.

Although websites and apps do need to follow WCAG for legal reasons, merely complying with SC 1.4.3 doesn’t ensure that contrast will be high enough to enable everyone to read the text. In addition to what Steve explained above, Somers’s research has found that the WCAG formula vastly overestimates contrast when at least one of the colours is close to black.

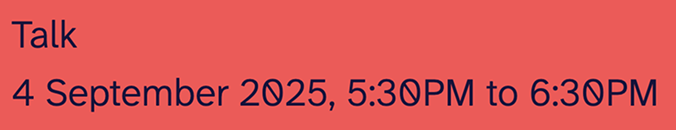

Here's an example of something WCAG approves and APCA rejects.

The image is a small bit of a screenshot from a website, indicating the kind of event and the date and time, in text against a solid background. As measured by the colour picker, the text is dark-purple and has a hexadecimal value of #141338, and the background is a medium(ish) warm red with a hex value of #D9645E. The WebAIM contrast checker gives this combination a WCAG contrast ratio of just over 5:1, which easily passes, even for normal-sized text. But the APCA checker calculates contrast as perceived by the eye — and says that this combination should be used for “spot and non text only” (in other words, it’s not for text of any kind or size). My 72-year-old eyes find this combination very hard to read, and they strongly agree with APCA.

For now, though, the WCAG algorithm is what the standard gives us, and we need to ensure that, at a minimum, our colours comply with it. This does not mean that if WCAG says a combination is OK we should feel free to use it — the WCAG formula may approve a combination that actually makes text hard for many people to read. The best approach is to use both checkers — WCAG for legal compliance (for now), and APCA for actual accessibility.

Two last thoughts to leave with you

Applicability. Despite the word “Web” in the standard’s name, many of the WCAG success criteria apply to other digital content as well. In particular, I find the contrast SC very helpful for PowerPoint presentations and for headings and graphs in Word documents. (Word’s default heading colours don’t always meet the standard.)

Ubiquity. As you can probably imagine, I’ve become very quick to point out instances of inadequate contrast when I see them — and I see a LOT of them. In fact, it has become a kind of a company joke how often I do that. I strongly suspect that my epitaph is going to read, “She alerted people to colour contrast issues”.

Further reading

- Contrast and Color Accessibility, by WebAIM

- Why WCAG Color Contrast Isn't Always Accurate, by Evan Levesque on LinkedIn

- The Myndex research content, and in particular

- The Easy Intro to the APCA Contrast Method (note that, for the most part, the Myndex content uses the word “readability” to refer to legibility)